Recovering Experts

Posted Jan. 29, 2023 by Maya Weeks and Dave GriffithsDave Griffiths of Then Try This, a Cornwall-based non-profit organization working towards a world with equitable access to knowledge, and Maya Weeks discuss everything from transporting Raspberry Pis on Sonic Kayaks—it involves platforms inside waterproof boxes to allow for condensation to settle at the bottom of said boxes—to reenvisioning citizen science as a way to distribute research skills beyond academia and affect local policy.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Part 1: Tools for understanding and engaging with the environment

MW: What do you need to make a Sonic Kayak? And why make a Sonic Kayak?

DG: To make one, at the moment, the latest one is quite a lot — a kit of a lot of different sensors, some of them you have to make yourself, and some you need to buy. But to start with, they were simpler, I think we just had a GPS and a temperature sensor. Just to sort of test what was going on. Oh, and a hydrophone. And I would say actually the hydrophone is probably the most important thing, or the most interesting thing. So you could get away with just a hydrophone and a Zoom recorder, headphones, and you’d get quite a good Sonic Kayak experience, I think.

MW: Have you overheard—or maybe not overheard, heard—any marine flora with your hydrophone? Any seagrasses or seaweeds scootin’ about?

DG: Well, yes and no. So, most of the places that we’ve been doing this are pretty damaged, so we are more interested in recording underwater noise pollution from things like boat engines. What we do hear around in Cornwall, there is quite a lot more life if you kind of just escape the built-up areas. We’ve heard what we were told might be snapping shrimp, when they do their thing, cavitation, I think, in the water, and it makes this sort of crazy clicking sound. When we were testing it, at one point, I think we were just having a barbecue on the beach with some friends and I just took the hydrophone down and, just sort of put it in the water to see what I could hear in the evening. And I saw a seal swim past and I heard this really weird sound and I thought, “I’ll record that, it must be something that was associated with the seal”. And put it on Soundcloud and we sent it to all of the audio researchers that do marine audio stuff, and they were like, “No it’s nothing to do with the seal, it’s some kind of fish! We don’t know what it is”. So it’s like, you just, one evening, drop a hydrophone in the water and you record something “new to science”! *laughs* That’s kind of interesting, that it’s one of these areas where we know so little.

All the places that people kayak are really important, in that they’re often where—tidal estuaries and things like that—the fish breed, so it’s where all the impacts of climate change are happening. But if it’s not open ocean and easily visible by satellites, you can’t really get anything on it. So they can put out stationary buoys that are doing 24-hour temperature measurement or doing sound recording, but they’re often expensive so you can’t get detailed spatial information as you’d need so many of them. So it’s really a case that people who are kayaking can provide this.

MW: That’s amazing and makes me want to ask if you could speak to the possibilities that those relationships between art and science open up, as far as your justice-oriented work goes.

DG: It becomes really apparent that the whole idea that arts and sciences are different is a very, very recent concept. You only have to go back a couple hundred years and they were the same thing; you’d have the academy of the arts and sciences and you’d have all of this very much understanding that they’re trying to approach the same problems and they need to be in the same room together. With the kayaks, the best thing there is that often we’ll have people interested in computer music, or kind of experimental sounds, and then scientific researchers, but there’s like a third group that we never sort of really realized before, which is all the kayak enthusiasts! And they’re in their comfort zone. The kayak instructors are just amazing to work with, and kind of constantly teaching you, like, how to triangulate to figure out where you are, you know, when the GPS doesn’t work, and all this kind of knowledge. And it sort of means that the musicians and artists and scientists involve are kind of put on the same level, which works quite well.

I think for our approach, it’s been much more to kind of flip things around a little bit and using arts or kind of different approaches to science to kind of challenge science to ask new questions and put researchers out of their comfort zone. And you definitely do that on a kayak! laughs

MW: I was reading through Then Try This’ absolutely amazing website archive, which I was just completely blown away by. And was reading something about diversity of sectors in one of the texts and I was wondering if you could speak to that theme, and how important that is for Then Try This’ work and commitments.

DG: Yeah, so that’s something very much that is a line that we can draw straight from the FoAM network’s approach to things. And I think, so Amber and me, I guess a similar kind of thing to all the people in FoAM, was that we’re both recovering experts. We’d kind of reached that point in our careers where, you could just kind of map out, you just knew your own rails, right, you kind of know where you’re going to end up. And that’s just, the moment that happens, I mean, Amber left her academic career literally on the day that she got tenure. So she did all of the hard work to get there and then yeah that day it was like, “Nope. Jump off.”

MW: That’s really lovely to hear. I feel like I personally and probably many more people could do with examples of celebrating, not just generality, but really, really deep curiosity, but in multiple directions. It’s part of why I was really excited to get in touch with FoAM. That also kind of brings me to, “What role does collaboration play in this work for you all?”

DG: I think we’re much more motivated by who we’re working with than what it is. We couldn’t redo the Sonic Bikes project in Cornwall because it’s really, really hilly here and it’s just not fun to cycle, so we had a joke that we put them on kayaks and then we actually sort of thought, “Okay we’ll apply for a little bit of money, run a little workshop, just run the bike system on a kayak and see how people like it,” and then very quickly it became apparent that where we were doing that, it was incredibly difficult for marine researchers to get fine-scale data on things like water temperature. And so suddenly all the people we were collaborating with were researchers, so that was more like, “Well clearly we need to be doing a lot of this,” but maintaining the connections with Kaffe Matthews and keeping up the sonification and experimental music side of things.

And then a really good example of that was when, there’s a local kayak club that specializes in working with visually-impaired people, giving them confidence out on the water, and there was one day when Clare Eatock, who runs that group, walked into our studio with a funder and said, “We’ve seen what you’re doing, and we want you to apply with us for this money,”. Which never happens! Like, when does that happen!?

And they were just brilliant, because that wasn’t something that we’d ever have thought of. Like, I was quite dubious it was going to be good enough for that group of people to use, especially with safety, and suddenly having to think about the accuracy of the GPS and things. But that was something that she saw—that she really thought there was something there—so we kind of went along with it. And the visually-impaired kayakers that she was working with told us how they wanted to use it, or how they could use it, and they played around with it, and eventually managed to use it for direction-finding. So I think the best projects are where you don’t really think too much about what it is, you just think, “This person is really interesting”, or, “this group of people is really interesting, we’ll just see where it goes, because it’ll be fun even if it doesn’t work”.

Part 2: Instruments for sound art and environmental mapping

MW: I’m curious about the biggest obstacles and challenges in adapting the bikes to the kayak context, as well as what kind of different knowledges and expertise were involved, if you’re willing to speak to that.

DG: Yeah, sure. So the electronics, the programming, all of that is kind of boring, that was all fine. The absolute nightmare was waterproofing.

MW: Yeah, I was wondering! *laughs*

DG: *Laughs* And we learned that the hard way, because the first time we did it, it was a disaster. We put them in waterproof boxes. We put sealant around the cables, I think. But the speakers were just kind of, like, how do you waterproof speakers? We just kind of had them open but with a top, like some horns on them, that would protect them from splashes and things. So it was splash-proof, pretty much. And on the first day we did a public event, it was beautiful sea, it was calm, everything was wonderful. And then on the second day it was a little bit too rough, and the first group of people were really keen, so the instructors were like, “Okay, let’s take them out anyway”, and they all capsized, and it was the worst. Like we just had bits of stuff washing up on the beach. I mean at the time we weren’t really worried because it was more worrying that the people were in the water but we kind of had everything wash up on the beach, and it’s a really physically demanding project, because you spend all your time carrying kayaks around, setting up tents, talking to people as they’re putting wetsuits on and stuff like that. And suddenly to have all of this happen…

And then with building our own turbidity sensors, it’s all about encasing all the electronics in resin, which is a whole other kind of world of materials that we had to kind of pick up and then teach people about, because they’ve been building them. So definitely the majority of it was the waterproofing; it was also just stuff with building things for that environment and fitting on lots of different types of kayaks. We realized that you can make your own straps. And then it turns out that that saves people a lot of money because it’s really expensive buying all the webbing for like the seats and all of that kind of thing but it’s really easy to make it yourself.

MW: Yeah, I was wondering if you guys had bought all waterproof electronic equipment. It just seemed really, really complicated so it’s interesting to hear about the, “No, we had to figure out how to waterproof everything, there was a lot of trial and error, people capsized…” I was imagining things getting rusted and people getting shocked and I was just like, “Aw, man, that’s so intense”.

DG: Yeah, when we work with the visually-impaired people, everything has to be completely safe, so we had to run tests where the instructors would take the system out and do rolls with it and capsize it deliberately and check that it all worked. And they happened to do that on the day when it was one of the worst storms coming over the country. And because they’re all really professional kayakers that do this as sort of a side job, they’re like, “Yeah of course we’re going out!” So it was good then, because then we actually had it properly tested by people who weren’t scared of doing it.

Part 3: Citizen science and games

MW: I have a question about the value and importance of citizen based-projects and game-based projects. I’m wondering what these approaches can do that other approaches can not.

DG: Amber’s got a really good diagram of citizen science science and it kind of stretches from, on one extreme it’s crowd-sourcing, so it’s like, you just want to get thousands of people trying to solve this problem. That’s kind of almost the lowest level, but that’s sort of what a lot of scientists think citizen science is: let’s get “the public” to solve our problems. And that’s kind of not really what we’re interested in. And then it goes all the way to, like, the sort of gold standard citizen science approach, where people are actually coming up with the questions that they want answered. And we’ve been doing this where pair up researchers and local people from different professions and they’ll come with questions that they want help learning to answer. And then that can actually lead to whole new sorts of research projects. But it also leads to changes in the law and things like that, so suddenly you’re making all of this kind of stuff possible.

MW: Amazing.

DG: And that’s the AccessLab project. And the thing about that is where we have somebody that wants a question answered, we’ll pair them with a researcher that hasn’t got a background in that thing, because then they have to learn with the person. Because they don’t switch on teaching mode, because that’s the worst, if you’re working with an academic, and they go, “Ah! I’m teaching you!” *laughs* “Sit there and absorb my knowledge!” And if it’s something that they’ve not done before, actually the important thing is, you know, “Where can I look for papers”, and, “Can I trust this author? What else have they published? Where have they published? Who are they funded by?” and all these questions that 99% of the population don’t have so much experience asking. So that’s our sort of, gold standard citizen science project where it’s actually the ‘citizens’ driving the science rather than the other way around.

So that’s really the knowledge that the researchers have that they don’t realize they have. And they don’t realize how important that is. We’ll be working with people who can then present all of the papers that they’ve found together as evidence for something that they need changed, that’s going into law, courts… for one project we had sort of evidence given to lawmakers locally for some changes as well.

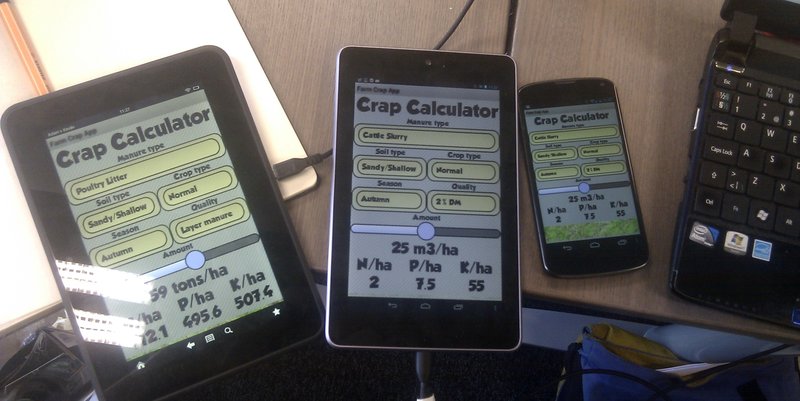

MW: Did you guys come up with the Farm Crap App trying to meet a specific need; was it something that grew out of various experiments? Could you tell me a little bit about its origin story as, like, a practical entity that’s also creative?

DG: Yeah, so, that’s an example of something where somebody very much came to us with something that they wanted. And that was this amazing college in Cornwall, called Duchy College, and they have an incredible history. They come out of, I think it was after the Second World War, when there was rationing, and food was really hard to come by. They have all these experimental agricultural fields where they’ll be constantly running different experiments and trying out different seeds and different methods of cultivation and things like that. But they also train farmers as well. So they’re training up young farmers and some of them go on to be researchers and some of them will have their own farms . I think a world expert in micro-propagation is based there. So like growing things from tiny fragments of plants, really rare things. So really that project is as much about them really understanding farmers and what they need but also their humor and how to talk to them, which is very different from a lot of academic, or a lot of research sort of things where they very much see themselves as a separate field to “the public.”

The problem that’s being solved there is to get the farmers using natural fertilizers. And the reason that they don’t is because of the regulations, mean that they have to report what they spread on their farms, and if an inspector comes along and they’ve put too much on they can be fined for that. So to avoid putting too much on, it’s much safer to buy bags of fertilizer that come from petrochemical industry because they have the numbers written on the side. And you feel much more comfortable that you’re not going to get fined.

The thing with that for us has been really understanding that setup, the fact that you’ll have farmers that own the farms, who have the contractors that do the work, you’ll have the landowners, so often the farmers will be renting it from the landowners, and then you’ll have the regulators, then you’ll have a whole industry of people contracted to do soil testing. And kind of learning where we fit within that, and where we’re sort of taking power away from one group and giving it to another group, that’s been a kind of real learning process, lots of workshops and actually just getting farmers and unions and regulators all in the same room has been amazing, because you just get them talking, and then you can’t stop them! You kind of give them something to work on together, to kind of draw out the relationship and things, and suddenly they’re just — we had to, like, push them all out to have lunch at one point.

MW: That’s so amazing.

DG: It’s a really lonely profession, that’s the other thing that people don’t realize. They have like the highest rates of depression and suicide and things like that. It’s not really the cozy life that we like to think.

MW: Was it important for you to understand this “language of farmers,” as you’re kind of putting it, and also to know, like, the language of kayakers, as well as, say, the language of experimental music, or was that stuff that you were able to pick up along the way?

DG: So I think with the farming it was very much that we just have to listen really carefully to what the people we were working with, what the researchers are telling us, it is much more a commission-based thing where we do what we’re told. But, having said that, there is a way that we approach it because we’re based in a rural place, and we’re, you know, hundreds of miles away from the nearest built-up kind of city. Being rural ourselves immediately gives us an ability to kind of do that work.

MW: I’m really interested in and excited about Then Try This’ work with local policy around climate change and pollution. I have a question about how to bring more, I think you called it scientific access, or evidence-based data, into decision-making. While knowing that evidence is always subjective, I was wondering if you could talk a little about that for, say, somebody with research skills who wanted to offer that to policy land.

DG: A few years ago Amber was on our local parish council, which is like, the people who make decisions for the town we live in and the one next to it. So very, very small-level. Which I always found quite funny because she also worked at European Parliament and Westminster as well, and it’s kind of similar. It was discovering that while, obviously, the sort of national-level politics have access to research, how much they listen and how that exactly works is a whole ’nother story. But local policymakers don’t have any support for this at all. So they’re just bumbling around like the rest of us, trying to work out… they don’t really know what they should be reading, or what’s out there or anything. And so one of the things that we’ve been doing in the AccessLab model is actually asking people where they find their information. So one of the really nice exercises we do—and we do this with the policymakers but also the researchers—is saying, “You’ve been diagnosed with leprosy. What’s your next step? Where are you going to look for information?” And what’s really funny about this is that researchers who aren’t medical researchers, they look in exactly the same places for information pretty much as policymakers or whatever. It’s kind of showing that none of us really know where to find information.

MW: I didn’t know that local council members wouldn’t have access to data the way that national ones would.

DG: Yeah, and the shocking thing in the UK is that even doctors don’t always have access to paywalled journals. So as soon as something’s behind a paywall, it’s completely useless for anybody that isn’t in a university. Which is ridiculous, because a lot of the really important stuff is paywalled. A lot of what we do in that project comes down to teaching researchers how to talk to people and how to actually be helpful. And it is a lot of that, like, not getting them to teach, and understanding that their years and years of understanding how knowledge is judged and how to find effective information is a really important skill, and to elevate that rather than how much they know about that specific bacteria that nobody’s ever heard of. So a lot of it is in just sort of reframing it for the researchers so that they see things a slightly different way. We’re trying to get the project that will do this on a wider scale off the ground, to roll this out in a few more places. Because we’ve had really good success doing it in small trials and getting actually cross-party support; across the political spectrum we’ve had people involved in the project, which is also, I think, really key.

MW: Does this make you optimistic about future politics in the UK?

DG: That’s a complex one. I think one of the things that I do is, I hadn’t really realized, is, to some extent, how I think the tiny-level, local—and I think it’s probably the same in the States, in a lot of countries—politics is actually probably where most of the decisions that affect most people are made. So the power is actually slightly higher than you’d think. And it’s just stuff like, you know, how’s the rubbish collected, who gets to build where, all those kinds of decisions are actually quite outsized compared with a lot of the things that the national-level politics is about. And a lot of the problems to deal with on a national level are never going to be solved. Whereas the problems on a local level you can actually have quite a huge effect quite quickly. So I wouldn’t say optimistic, but there might be more room for improvement than we think. laughs

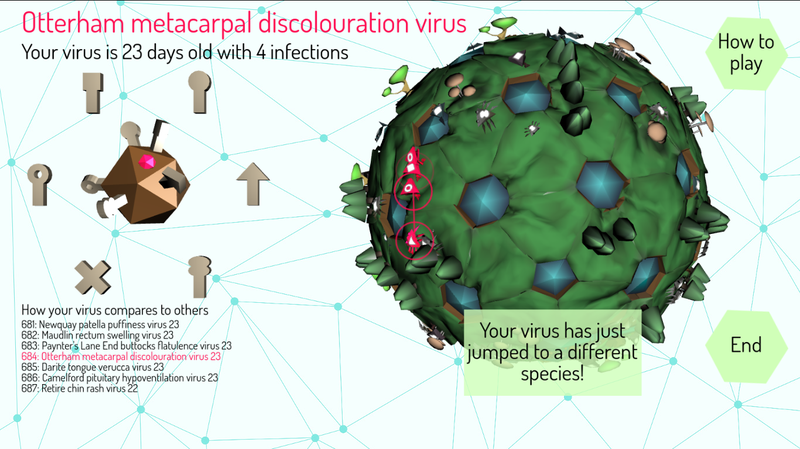

MW: I have a question about the game Viruscraft II that you all were coming up with right before the pandemic started. Did you see that game having an affect on how people handled the pandemic situation in the beginning?

DG: At the height of the lockdown, we did a couple of Zoom sessions where we sent out the game as a link, asking people to try it and give us feedback about how it changed how they thought about viruses. And then as a kind of opportunity when they’d done that, if they did that, was to then meet the two virologists that we were working with and ask them any questions they wanted about viruses. And that was super interesting, because we had everybody from, I think we had, another researcher had lots of really techy questions about their particular research. But I think we had some skeptical people, some vaccine skeptics and people who were a little bit unsure about it all, and that was really good to be able to get them all in the same space and asking questions. And actually just to ask people who work on viruses all of their life, and say, “Are you washing your fruit and vegetables when you buy stuff at the shops?” And then they’d go into sort of, “Well, yeah, I started off doing that but now I can’t be bothered, and…” *laughs*

The one we did before the pandemic, it was really good as a way of getting kids to be playing something together. We went to a science festival, we had loads of families, all the kids playing it and all the parents asking us about vaccination. To be like, “I’m not really the person to ask, but this person here is! That’s their job.” And you could kind of make a space for those conversations to happen. So lots and lots of worried parents at that point asking about—this was before COVID—the ramifications of the different vaccinations they’re supposed to give their kids, and worrying about that. Again, it’s a bit like AccessLab in that way. It’s just creating a space where the kids are occupied, there’s lots of worried parents, and then there’s some researchers who can sort of be the voice of some kind of information.

MW: That really seems to be the overarching theme of your work — bringing disparate groups and individuals together and prompting conversations that wouldn’t all otherwise have the opportunity to happen.

DG: I think so, yeah. And I think that’s something that is a cause of a lot of problems, a lot of, more and more, divisions between people that, you actually get them together and they’re all worried about the same stuff.

MW: Thank you so much, Dave!

This text is featured as part of FoAM's Anarchive

Created: 27 Jan 2023 / Updated: 30 Jan 2023